From about the early 17th century until the end of the 19th century, format was used in the trade to indicate a book’s size and shape. In a bibliographical context it indicates a book’s structure, i.e., the relationship between the sheets of paper on which it was printed and the individual leaves created when the sheets were folded into gatherings. For example, in a folio (20) each sheet was folded once, in a quarto (40) twice, in an octavo (80) three times, the resulting size being respectively a half, a quarter, and an eighth that of the original sheet.

The sheet is the printer’s unit; the gathering (the group of leaves formed after the printed sheet has been folded to the size of the book) is the bibliographer’s unit—it has come to us bound up with other gatherings into a book. In determining format, one is thus engaged in a mental “reverse engineering” of the book back to its constituent printed sheets. We must “unfold” the gatherings in our mind’s eye. Now it should be noted that gatherings may be made-up of multiple sheets, or half-sheets, but here I am concerned only with straightforward gatherings made-up from single full sheets.

Pictured here is our “cheat sheet” (a training tool from Rare Book School) depicting a printed sheet imposed in common 120 format:

Duodecimo format: inner forme

The sheet is depicted schematically to show the direction of its chain lines, its watermark, and its deckle edges—three distinguishing features of paper made by hand in a paper mould during the hand-press period—and the imposition of the pages. To make a duodecimo gathering, the sheet is cut or folded across its long side into thirds, and then folded twice the other way. Common duodecimos were folded by removing an off-cut (one of the outer thirds) which was folded separately and then quired or “tucked” inside the remainder of the folded sheet. This will result in a gathering of 12 leaves/24 pages. The chain lines will be horizontal, and the position of the watermark (if present) will typically be found in the upper fore-edge of leaves 7 and 8, or of leaves 11 and 12.

Why present an example of duodecimo format? When training students, I begin with the simpler examples of folio, quarto and octavo. Here I’ve gone straight to duodecimo because we have a book from the James Wilson Bright collection with wear and tear to the original binding that allowed us to easily remove and “unfold” the first gathering, and to reconstruct its six pairs of conjugate leaves (without causing further damage!) back to its original state as a full sheet after it went through the press.

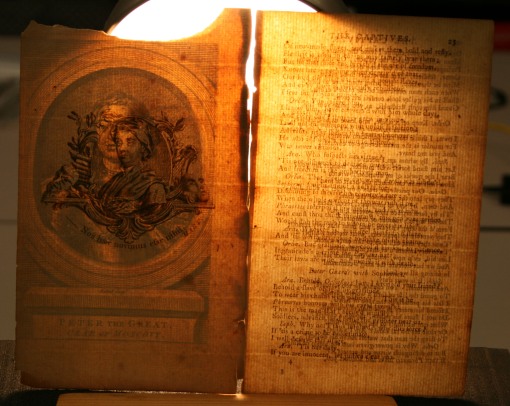

Pictured here is that first 12-leaf gathering unfolded, taken from Bright’s 1772 edition of Plays written by Mr John Gay. London: W. Strahan, T. Lowndes—(ESTC no. T13746):

Plays written by Mr John Gay (1772): the first gathering

Although the actual size of this book (with an uncut height of 17.5 cm) is closer to octavo format (duodecimos are typically smaller), the imposition of the twelve pages shown here exactly matches the RBS facsimile. Both examples depict the inner forme, beginning with pages 2 and 23 on the first pair of conjugate leaves (A1 and A12) in the upper left corner of the sheet. This first thing to notice about this pair of leaves is the frontispiece depicting John Gay (printed on the second page of the first leaf—i.e., leaf A1 verso. The first page on the other side is blank). This is a copper-plate engraving. With the sheet unfolded like this, it is easy to verify that leaves A1 and A12, separated along the gutter, are indeed conjugate.

This answers the bibliographer’s first question: Was the frontispiece printed on a separate sheet of paper from a copper plate on a rolling press and inserted (which was the typical practice at this time), or was it printed on a leaf integral to the letterpress gathering? Although it is not usual for a single full sheet with 23 pages imposed for letterpress printing (a relief process) to be sent through a rolling press (an intaglio process) just to print one copper plate engraving—it is not unusual. What is unusual about this particular frontispiece is this:

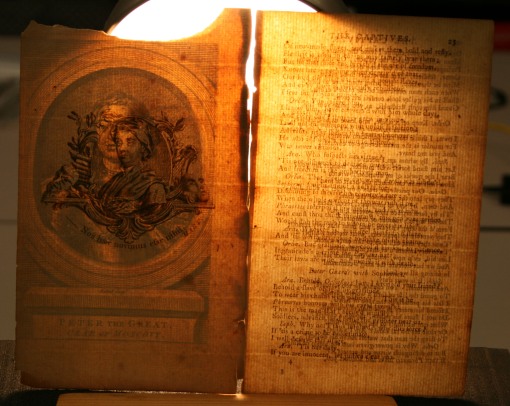

Conjugate leaves A1 and A12 (pp.2/23) in normal light

Conjugate leaves A1 and A12 (pp.2/23) in direct light

Who is that peering out from behind Mr Gay? Held up to direct light one can see that the horizontal chain lines of both leaves match across the gutter. One can also see and feel that the leaf with the frontispiece actually consists of two identical leaves of paper fused together, but it is impossible to see how the one was overlain atop the other. What is going on here?

When viewed normally the engraving behind Mr Gay is discernable only as a faint shadow embedded within the paper. At first glance I thought it had been offset from another sheet. Held up to direct light this shadow engraving can easily be identified as “Peter the Great / Czar of Moscovy”—a copper plate line engraving by John Hall (1739-1797).

I suspect that the full sheet was first printed letterpress; that the wrong copperplate engraving was used when the sheet went through the rolling press, and that a leaf with the correct engraving—“the Cancellans”, was pasted over “the Cancellandum.” Or was it intentional, this juxtaposition of John Gay with Peter the Great? After all, both men were contemporaries, and Peter the Great was, in fact, gay, but I did not find any historical evidence of a direct link between them.

What is the bibliographical significance of this, if any? Is this copy-specific attribute unique? Can anyone explain how the leaves were so expertly pasted together? Not only are the chain lines seamlessly matched, so too are the laid lines! Because the fusion is perfect, the effect is magical. Peter the Great appears like a ghost embedded in the grain, like the image of Jesus in the Shroud of Turin.

Our Special Collections staff all agree that this is a gorgeous binding: with its embossed purple-brown cloth, and the colors in the dye stamp that gradually change from a reddish-bronze to gold and play delicately with the light. The whole effect is a stunning use of hue and iridescence.

Our Special Collections staff all agree that this is a gorgeous binding: with its embossed purple-brown cloth, and the colors in the dye stamp that gradually change from a reddish-bronze to gold and play delicately with the light. The whole effect is a stunning use of hue and iridescence.